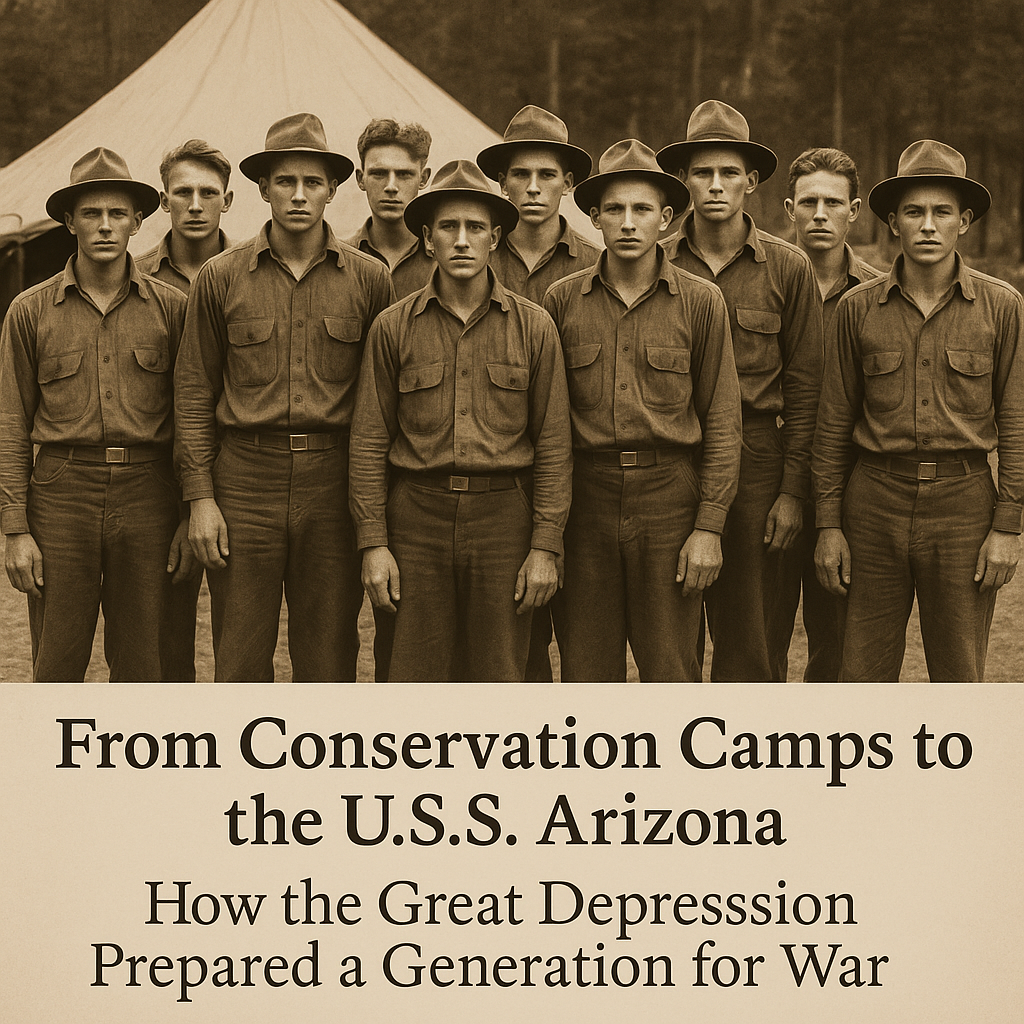

From Conservation Corps to the U.S.S. Arizona: How the Great Depression Prepared a Generation for War

From Conservation Corps to the U.S.S. Arizona: How the Great Depression Prepared a Generation for War

Before they served aboard the U.S.S. Arizona, many young men first found purpose and discipline in Depression-era jobs like the Civilian Conservation Corps. In many cases, these federal programs led them to military service.

Written by: Bobbie Jo Buel

Before they enlisted in the Navy, many of the men on the U.S.S. Arizona served in the Civilian Conservation Corps or other Depression-era federal jobs programs.

Unemployment was 20 percent in 1935, a time when many of the future Arizona sailors and Marines were in their teens. Nowadays, most teens are in school. But in 1935 just 60 percent of high-school age students graduated. Which means many quit school in search of work. It was tough, though, to be a teen without job skills competing against experienced men in their 30s and 40s in the depths of the Depression.

And so President Franklin Roosevelt created the Civilian Conservation Corps, commonly known as the CCC. It employed single men 18 to 25 to plant trees, build roads and trails and make other improvements to public land, forests and parks. The men lived at camps across the country and were provided a bed and three meals a day. Of their $30 monthly pay, $25 was sent to their families. ($30 then is equal to about $700 now.)

A few Arizona men worked for a similar program, the National Youth Administration, which mostly employed them in part-time jobs while they were in school. James Frederick Sooter earned $6 a month in 1938 as a door monitor at the junior high school in Weslaco, Texas. He graduated in 1940 and joined the Navy in June, first serving on the U.S.S. Nevada and then starting in November on the Arizona.

Other Arizona men – and even more of their families – worked for the Works Progress Administration. It hired people 18 and older, including some women, in all sorts of jobs. A main criteria was that a local agency had to declare that they needed federal assistance.

CCC jobs, which usually lasted a few months to a year, became a pipeline to the military. Camps were run in military fashion and some of their leaders were military men. Teens who did well in the CCC were viewed as good candidates for service.

Melvin Freeland Horn was one of them. He was two when his father and an older sister died of influenza a day apart in 1919. Years later a relative recalled that the family was so poor older brothers shared a pair of shoes and took turns attending school.

Melvin became the only one of his mother’s eight children to graduate from high school, which he did in 1934 at Sunbury High near Columbus, Ohio. His mother died the next year. Melvin worked on farms in the West and in Ohio and served in the CCC in Oregon. He enlisted in the Navy in October 1940 and went aboard the Arizona that December.

We are still combing through enlistment records, but it appears that nearly 10 percent of the Arizona men were first employed by the CCC.