Fathers of the Fallen: The Men Who Served After Losing Sons at Pearl Harbor

Fathers of the Fallen: The Men Who Served After Losing Sons at Pearl Harbor

Written by: Bobbie Jo Buel

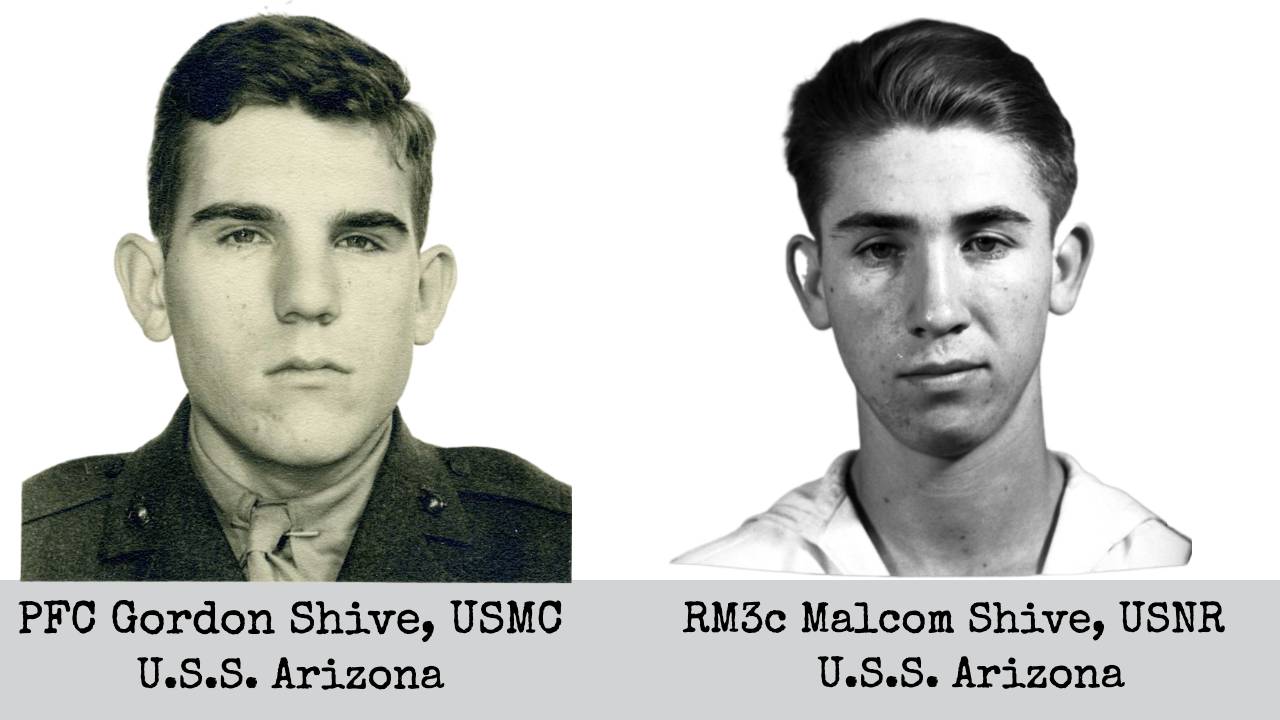

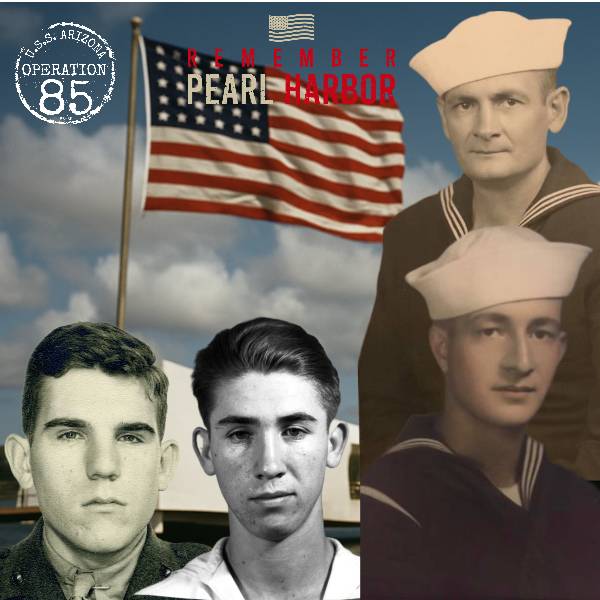

When he heard that his brothers, Gordon and Malcolm, were killed in the attack on Pearl Harbor, Robert Shive tried to enlist. He was 11.

He was 17, the legal minimum, when he succeeded. Robert served in the Navy for 20 years.

Robert Shive was one of thousands of brothers of the men killed on the U.S.S. Arizona who served in World War II, Korea and Vietnam. A few older brothers served in World War I.

But it wasn’t just brothers who enlisted or joined the war effort after Dec. 7, 1941. Fathers, mothers, sisters and wives did, too. Today we tell the story of a few of those fathers.

The day after George Edward Bromley and Jimmie Bromley were killed their dad, Walter, tried to enlist.

The Navy rejected Walter because he was 51 and the age limit for enlistment was 50. But when he learned officially that his sons were dead, he applied again and the limit was waived.

“It’s the happiest news of my life,” Bromley told a reporter. He’d been earning $8.25 a day at a Tacoma, Wash., door manufacturing plant, but gave that up to earn $2 a day as a carpenter’s mate. He served on the U.S.S. Colorado and at a fleet base in the Admiralty Islands until November 1945. His wife, Ruby, went to work as a shipfitter in their hometown.

Ernest Hubert Whitson Sr. was a craine operator in Cincinnati, Ohio, when Pearl Harbor was attacked. He quickly applied to do the same job at the Navy yard in Honolulu. Mr. Whitson told a reporter that he “felt everyone should do his part, and that was one way I can help.”

The World War I veteran had passed the physical exam and was waiting for his final job certification when a telegram arrived on Dec. 21 informing him and his wife, Elizabeth, that Ernest Jr., a musician on the Arizona, was missing. He was declared dead the next February. Both parents moved to Hawaii, where Mrs. Whitson also worked — as a nurse — for at least two years.

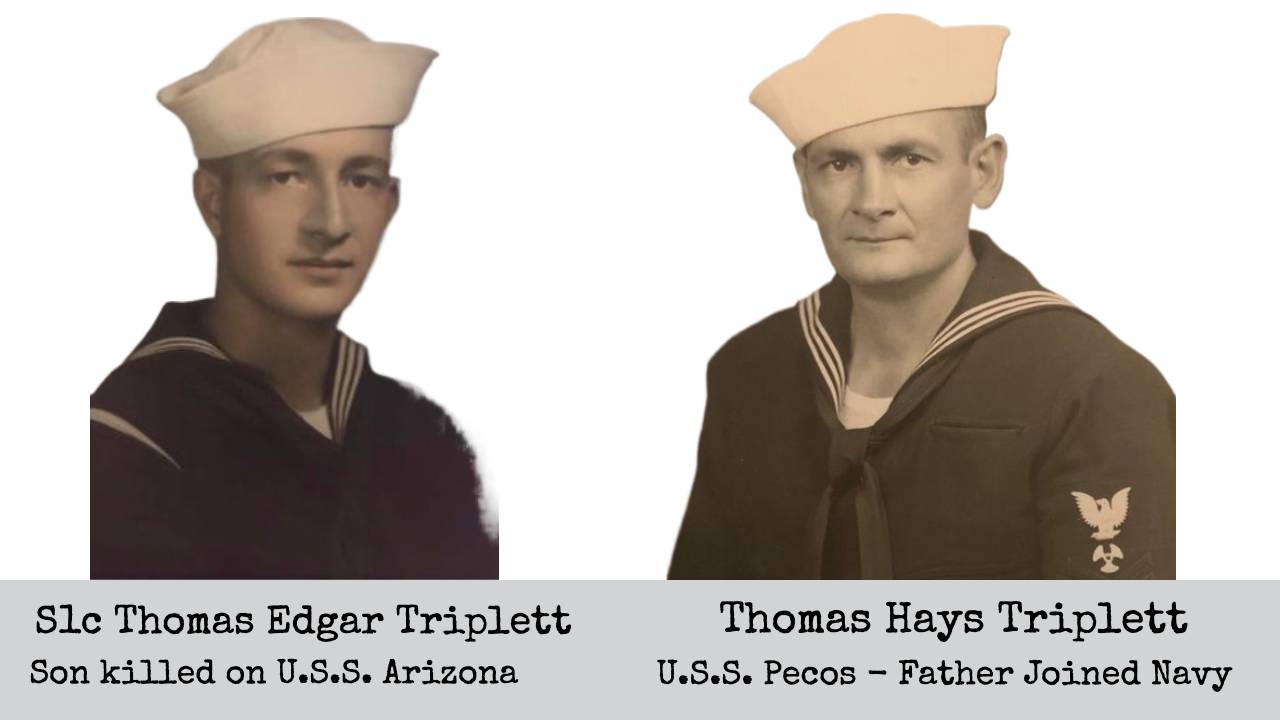

Two months after his only son, Thomas Edgar Triplett, was killed on the Arizona, Thomas Hays Triplett tried to enlist.

But he still had a wife and two daughters to support, and the only Navy job that paid enough to do that was in a construction regiment ashore. Mr. Triplett, who had a good civilian job as a locomotive fireman for the Missouri Pacific Railroad, would have none of it.

He wrote to Navy Secretary Frank Knox asking to be assigned to a ship in the Pacific. In July 1942, the Navy agreed and enlisted him as a watertender first class. He was well suited to the job. A watertender tends the fire and boilers in a ship’s engine room.

“I want to get into a fighting unit of the Navy, and the sooner the better,” Mr. Triplett told a reporter for the Hutchinson (Kansas) News.

“I can get along on cigarette money,” he said. “Just so my family gets along.” His wife, Lucy Yarnell Triplett, was left behind with a toddler and a teen-ager. She said she supported his service even though he had to take a $100 a month pay cut.

Mr. Triplett officially enlisted on July 30, 1942, and was assigned to the U.S.S. Pecos, an oil tender, until June 25, 1945. The ship survived repeated attacks in the Pacific and earned seven battle stars.

Operation 85 does not have a definitive list of fathers who served, but we know they performed a variety of jobs in the United States and abroad, ranging from shipfitter to gunner’s mate and from pharmacist to recruiter. The father of at least one sailor killed on the Arizona was already serving on Dec. 7, 1941. On that terrible day, Quintin Delgado Meno, father to Vicente, was aboard the U.S.S. Gold Star at the second largest Philippine island, Mindanao.

The Gold Star’s job was to supply Guam with everything from fuel to clothing. It finished loading coal that Sunday morning and was ready to head home when it received a confidential message: “Despite fact Gold Star ready to sail because of general situation inadvisable to start now.”

Quintin Meno served for 29 years until he retired in 1945.