History of the U.S.S. Arizona Memorial

The USS Arizona Memorial: From Idea to Icon

Origins: A Wartime Loss Becomes a National Obligation

When the battleship USS Arizona (BB-39) exploded and sank on December 7, 1941, she took 1,177 sailors and Marines with her. In the years that followed, the Navy removed much of the ship’s wrecked superstructure, but the idea that the nation should honor the entombed crew where they rest took hold and never let go. Early gestures of remembrance began on the hulk itself; in 1950 Admiral Arthur W. Radford, then Commander in Chief, Pacific (CINCPAC), ordered a flagpole mounted on the Arizona and directed that the U.S. flag be raised and lowered daily over the ship. On the ninth anniversary of the attack, a plaque was placed at the base of that flagpole. These acts formalized the Arizona as a sacred site and kept public attention on creating a permanent memorial.

The first systematic push for a memorial took shape with the Pacific War Memorial Commission (PWMC), established in 1949 by the Territory of Hawai‘i to raise funds and guide planning for war memorials—including one at the Arizona. PWMC’s creation gave the movement a charter, a committee, and a way to coordinate with the Navy and with national allies.

A lesser-known spark came from popular culture: Robert Ripley of Ripley’s Believe It or Not! visited Pearl Harbor in 1942, then used a 1948 broadcast to advocate for a permanent memorial and wrote the Navy pressing the case. His concept proved too costly and went nowhere, but his advocacy added momentum at a moment when the public’s attention was drifting.

Authorization and the First Fundraising Wave

Congressional authorization finally arrived with Public Law 85-344 (March 15, 1958), empowering the Navy to accept contributions, assist with design, and build the memorial once sufficient funds were in hand. Initially, no federal construction dollars were to be used—the memorial would rely on private and territorial contributions—though that stance softened later. The Territory of Hawai‘i promptly contributed $50,000 (and later another $50,000), while national publicity drives began.

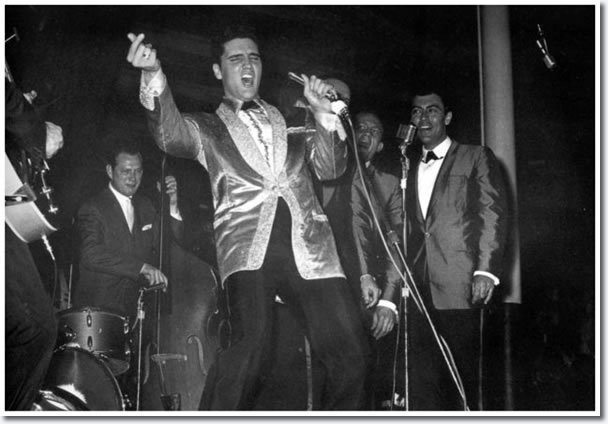

Two public events were pivotal. First, Rear Admiral (ret.) Samuel G. Fuqua, a Medal of Honor recipient and the senior surviving officer of the Arizona, appeared on the television program This Is Your Life in 1958. The broadcast—filmed in Hawai‘i—generated roughly $95,000 in donations and galvanized a nationwide base of donors. Second, when fundraising sagged, a single star revived it: Elvis Presley’s benefit concert at Bloch Arena on March 25, 1961, donated 100% of proceeds to the fund and, just as important, reignited national attention.

Grass-roots partners joined in. The Fleet Reserve Association teamed with the Revell Model Company to sell Arizona plastic model kits, raising another $40,000. Meanwhile, Hawai‘i’s congressional delegation pressed for a limited federal contribution. In September 1961, President John F. Kennedy signed legislation (Public Law 87-201) authorizing a $150,000 appropriation, closing the gap and ensuring construction could finish.

Choosing a Design: Alfred Preis’s Vision

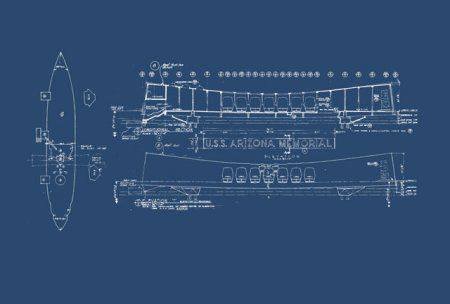

The Navy specified that the memorial should be a bridge-like structure spanning—yet never touching—the ship and should accommodate roughly 200 visitors at a time. Honolulu architect Alfred Preis, an Austrian-born designer who had been interned on Sand Island early in the war, produced the winning concept: a 184-foot white form with high, strong ends and a gentle sag in the center—a metaphor, he explained, for “initial defeat and ultimate victory.” Within the memorial, visitors would pass through an entry, then a light-filled assembly room, and finally into the shrine room listing the names of the dead.

Preis resisted overtly martial symbolism. The widely repeated idea that the memorial’s 21 openings represent a 21-gun salute isn’t his; he chose an odd number of trapezoidal openings to center the composition and provide airflow, and later adapted the “Tree of Life” motif as a universal symbol of renewal. The result is a space that invites quiet contemplation rather than dictates how to feel.

.

Elvis Presley’s Timely Assist (and why it mattered)

By early 1961, the PWMC’s campaign had stalled. Then Elvis Presley agreed to headline a one-night benefit at Bloch Arena—the very venue used for wartime court-martials and, in 1958, the This Is Your Life filming. Presley’s show on March 25, 1961 contributed about $62,000 (reported as $48–64k depending on the accounting) and delivered a publicity shock that re-energized national giving. Within months, Congress approved $150,000, and construction moved into its final stage. Elvis’s benefit is often credited with saving the project’s momentum at the critical moment.

Building the Memorial: Engineering and Craft

Cost pressures forced an incremental approach. Under Navy leadership at Pearl Harbor Naval Shipyard, crews drove reinforced concrete piles and built the substructure (pile caps, girders, and deck). Once additional funding was secured—including the 1961 federal appropriation—the Walker Moody Construction Company won the contract for the superstructure in October 1961. Final construction costs, including military in-kind work, totaled about $532,000.

Inside the shrine room, AMVETS installed the first marble wall of names, carved in Imperial Danby marble from Vermont. Later, when steel anchors behind the stone corroded in the marine environment, the wall had to be replaced—one of several significant maintenance efforts the memorial has required over the decades.

Dedication Day: May 30, 1962

Under bright Memorial Day sun, the USS Arizona Memorial was dedicated on May 30, 1962. Roughly 200 invited guests and hundreds more on nearby Ford Island heard Navy leaders, Hawai‘i officials, and clergy speak, with the ceremony framed by prayer, the Navy Hymn, and Taps. The new shrine presented the nation with a place to stand over the ship and speak the names of those entombed below. Contemporary accounts highlight survivors among the invited guests; press coverage notes an additional crowd of about 800 along the shore.

After the Dedication: Caring for a Living Site

The memorial instantly became one of Hawai‘i’s most visited places. As visitation climbed through the 1960s and 1970s, the Navy and partners concluded that shoreside facilities were essential to preserve the sanctity of the memorial experience. Senator Daniel K. Inouye and others championed a visitor complex, and in 1980 the present visitor center opened under a formal Navy–National Park Service agreement, with the NPS ultimately taking on day-to-day operation and curation. Today, the memorial remains a collaborative enterprise of the U.S. Navy and the National Park Service within Pearl Harbor National Memorial.

The Role of families, and the Public–Private Coalition Behind the Memorial

From the start, the Arizona’s families and shipmates were not passive bystanders. Survivors helped tell the story—most memorably Admiral Fuqua’s TV appearance—and veterans’ groups (notably AMVETS and the Fleet Reserve Association) raised money, installed and later replaced the wall of names, and advocated for proper shoreside facilities. Territorial and federal leaders—Governor William F. Quinn, Delegate (later Rep.) John Burns, Senator Daniel Inouye, Senator Spark Matsunaga, and others—translated public sentiment into legislation and appropriations. The memorial exists because families, veterans, civic leaders, entertainers, schoolchildren buying model kits, a territorial legislature, and Congress all pulled together.

Up until the formation of Operation 85, there were no organizations that represented the interests of the families of those killed and missing at the U.S.S. Arizona Memorial. Now Operation 85 and the Operation 85 Foundation have taken a lead role in representing the families of the missing crew and most importantly identifying the crew members that had been removed from the ship and buried as UNKNOWN at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific.

What the Design Asks of Us

Preis designed a sequence of feelings. Visitors pass through a compressed entry into a sun-washed hall open to the trade winds—rib-like concrete frames and odd-numbered side openings invite air, light, and silence. The center “sag” represents the nation’s darkest hour; the strong ends signal resilience and victory. At the far end, the shrine room lists the Arizona’s dead in marble, while a separate panel remembers crew who survived the attack but later chose to have their ashes interred aboard the ship. The space does not prescribe emotion; it makes room for it.

A Living Memorial

The Arizona remains the final resting place for more than 900 of her crew. Each year, the Navy and NPS host ceremonies where the ashes of surviving shipmates—by their request—are returned to the ship. Millions of visitors cross the harbor to walk the span over the hull and speak the names etched in stone. The memorial’s power endures because its creation story braided public remembrance, family advocacy, military stewardship, and civic leadership—and because its design invites each person to reckon with sacrifice in their own quiet way.

Passing the Torch to the Next Generation of U.S.S. Arizona Family Members

As we get further and further away from the 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, there is a chance that information and knowledge of family history from the U.S.S. Arizona and the attack on Pearl Harbor may get lost with each dying generation. It’s important to pass on your family history and instill the importance of those that served, and those that gave the ultimate sacrifice. The U.S.S. Arizona’s “Operation 85” Founder and Executive Director Kevin Kline, takes time at the U.S.S. Arizona Memorial to pass a torch to his two young daughters, honoring their fallen uncle GM2c Robert Kline at a flag raising ceremony on the Arizona Memorial in August 2022.

Teaching the Next Generation

Sources and further reading

- NPS history pages summarize the ship and the memorial and quote Preis on the design’s intent. National Park Service

- Administrative histories detail the legislation, funding, construction contracts (including Walker Moody Construction Co.) and costs. NPS History

- Photo sources: Hawai‘i State Archives (PWMC construction photos); Library of Congress (construction images, 1957–61); Naval History & Heritage Command (dedication and memorial galleries). FacebookThe Library of CongressNaval History and Heritage Command

- Fundraising: This Is Your Life (Admiral Fuqua’s 1958 episode) and Elvis Presley’s March 1961 benefit contextualized by the U.S. Naval Institute and other histories. USNI News

- Photos: US Naval History & Heritage Command; US Navy; Elvis Presley Enterprises; Operation 85