When One Son Wasn’t the Only Loss: The Families Who Gave Everything at Pearl Harbor and Beyond

When One Son Wasn’t the Only Loss: The Families Who Gave Everything at Pearl Harbor and Beyond

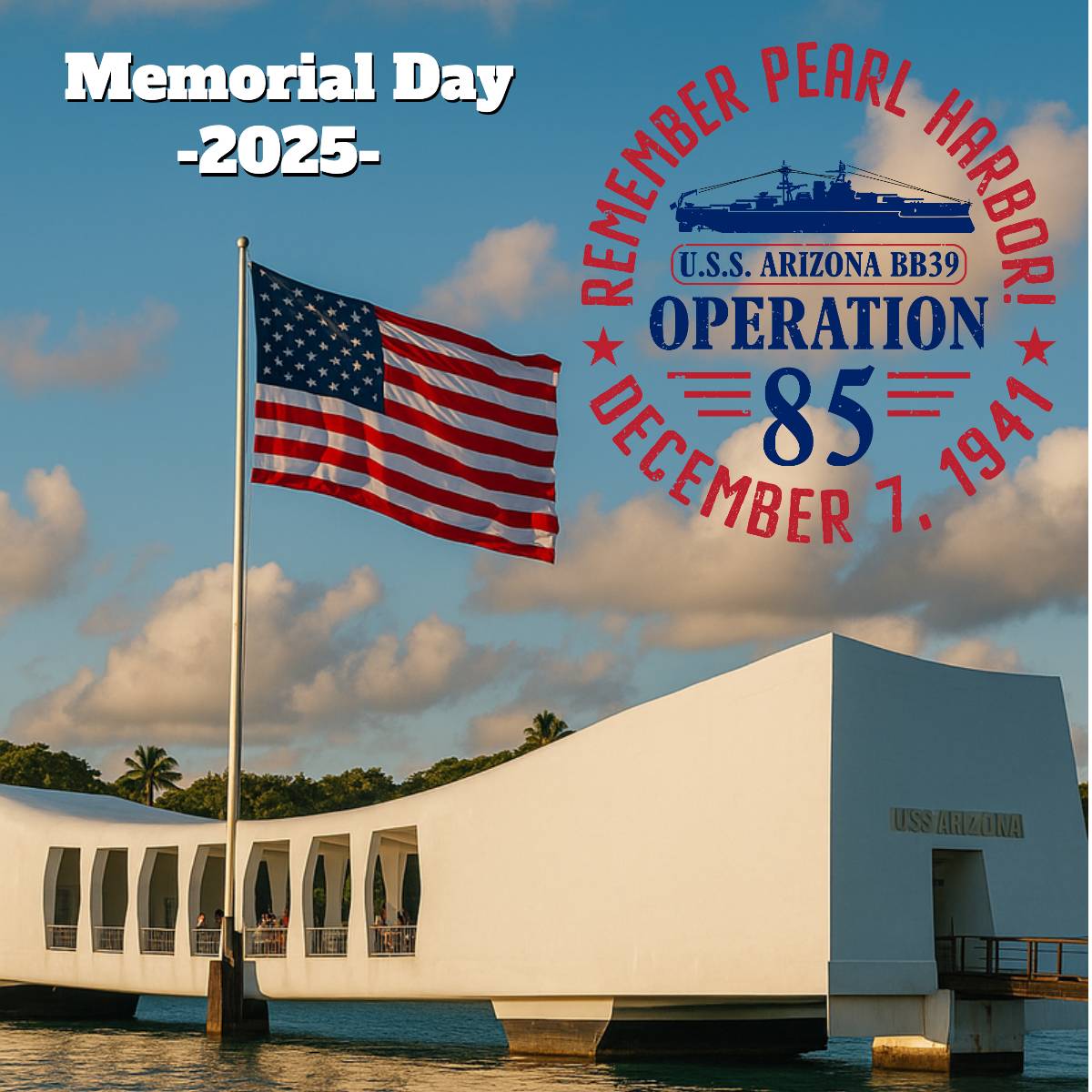

On this Memorial Day weekend we remember the men of the U.S.S. Arizona and their families, especially those who lost multiple sons to war.

“The boys over there are on duty 24 hours a day,” he told a reporter. “Everyone here should keep plugging for all the production we can get to back them up.”

Ralph Martin Gaultney was severely burned in the attack on the Arizona and died on Christmas Eve. He had been blown off the battleship and into flaming fuel oil.

His brother Leonard was killed in early August 1942 when his heavy cruiser, the U.S.S. Vincennes, was sunk in the Battle of Savo Island. Their mother, Nellie, died the next summer at age 54. Her daughter Laverne said “mom grieved herself to death.”

The LeRoy, Illinois, family’s loss grew still worse in March 1945 when a third son, David, a Marine private, was killed at Iwo Jima.

Max Edward Flory and his older brother Dale were both assigned to the U.S.S. Arizona. Max died, while Dale barely escaped. He had been on furlough to the mainland United States but was back in Hawaii that fateful morning preparing to return to the ship when the attack began.

In a letter to his family, Dale wrote: “It was the most unbelievable thing I ever saw, and now I have to keep going by the remains of the vessel, knowing it is my brother’s grave and that of a lot of my shipmates. But the flag is still flying on the remains of the ship. I did not expect to see the states again so soon, if ever, but by the time you get this I will be gone again.”

Dale did not see the family’s Bloomfield, Indiana, home again. He was killed in May 1942 aboard the U.S.S. Neosho, a fleet oiler that was sunk during the Battle of the Coral Sea.

Seven sons of Amos and Lillie Hilton fought in World War II. The first to enlist, in 1934, was Wilson Woodrow Hilton, a sturdy 175-pounder who represented his ship, the Arizona, in wrestling against sailors from other ships. He was killed in the attack on Pearl Harbor.

By then, two of his brothers, Amos and Paul, were also in the military — Amos in the Army Air Forces and Paul in the Army. Their father was so angry at Japan that he tried to enlist in the Navy, but he was rejected because he was in his late 60s.

Other brothers soon went into service: Boyce in the Army, half-brother Russell in the Coast Guard; Norman in the Navy; and the last, Berlin, in the Coast Guard in September 1943.

In 1944 the Hilton parents learned that Wilson’s body had been recovered from the Arizona, and they wanted it returned to their home in North Carolina. So when a clergyman visited their farm that August, they assumed it was to talk about Wilson. But Coast Guard chaplain L.Y. Seibert was there to deliver more terrible news: Berlin, 20, had been killed in New Guinea.

“When the time came for him to impart the real purpose of his visit, Chaplain Seibert, himself, says he would have preferred that the earth open up and claim him,” The Lincoln Times reported.

“In spite of the awful proportions of this blow, Chaplain Seibert says the God-fearing attitude with which these patriotic Americans received the news was an inspiring experience.”

The newspaper explained that about a year earlier the Hiltons had sold their farm for about $1,000 profit and bought a smaller one nearby. They had plans for the money, but ultimately decided to plow it into war bonds.

At least seven Hilton grandsons were also serving in the military by the summer of 1945 when Lillie presided over the honorary launch of a tug, the U.S.S. Salinan, at Charleston, S.C.

After the war, the bodies of Wilson and Berlin were returned to North Carolina. They are buried next to each other at Salisbury National Cemetery, about an hour east of their Catawba County farm.